Visits: 72

The Japan that Kansai Yamamoto showed the world in 1971 came as a shock: not subtle, tasteful, crafted of natural materials and worn by time. It was the Japan of souvenir shops outside popular shrines, stocked with tat in synthetic lamé; of firemen’s demon tattoos; and of woodblock prints of purple-clad ghosts. Yamamoto learned in time that these continued the five-century-old Japanese style of basara – meaning “way too much” and “wild rebel” – but when he was growing up in the 1950s they simply reflected a working-class taste, rougher than the country’s sober traditional aesthetics and westernised postwar aspirations.

The first major customer of Yamamoto, who has died aged 76, was luckily a westerner who got the appeal of basara and even knew quite a lot about Japanese kabuki theatre: David Bowie. Yamamoto busted out of Japan in 1971 to show an extraordinary collection at London fashion week of theatrical garments, gaudy graphic makeup somewhere between kabuki and Amazonian tribal, and comic-book presentation. London enjoyed his pop-art oriental exotic style, and his women’s clothes were stocked in the boutique Boston 151 on the King’s Road, Chelsea.

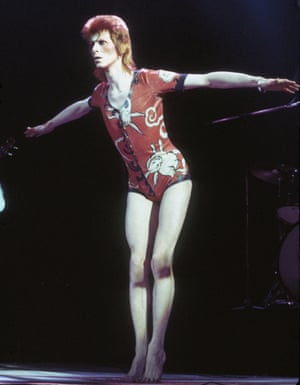

Bowie was creating his Ziggy Stardust persona that year, and the crucial red colour of his mullet haircut, perhaps even its spike, was adapted from a kabuki wig worn by the model Marie Helvin in a Yamamoto shoot for Harpers & Queen magazine. Bowie, advised by the stylist Yacco Takahashi, bought a few pieces from Boston 151 for his tour wardrobe in 1972.

Kansai Yamamoto, with the ‘Tokyo Pop’ jumpsuit he designed for David Bowie, at a Bowie exhibition in Barcelona, 2017. Photograph: Alejandro García/EPA

The twin sensibilities met when a friend of Yamamoto’s phoned him in Tokyo at 4am to tell him he had to reach New York soonest to see an “interesting person”. Yamamoto cancelled all plans, dashed for a plane, and went direct from JFK airport to a front row seat at Radio City Music Hall as the show started. Bowie descended from above, wearing Kansai clothes: “Some sort of chemical reaction took place: my clothes became part of David, his songs and his music.”

They met after the show, and again when the Bowie tour reached Japan, where Yamamoto took Bowie and the great kabuki onnagata (a male player of women’s roles) Bandō Tamasaburō out to dinner, all three around the same age, quietly exchanging ideas on performance. He began to design Stardust and Aladdin Sane costumes for Bowie in the basara manner, including a knitted jumpsuit based on Japanese labourers’ workwear, a mighty robe with Bowie’s name in giant kanji characters, and the “Tokyo Pop” jumpsuit inspired both by Oscar Schlemmer’s Bauhaus ballet designs and the galligaskin breeches of Portuguese sailors and merchants trading with Japan in the 16th-17th centuries; local artists’ depictions of those foreigners in their grotesque garments were among the foundation of basara style.

Press studs held the jumpsuit together so that, kabuki-style, stagehands could pull it off instantly to reveal a contrasting costume. Yamamoto designed them all as if for a woman – none has a front zipper. They remain among the most memorable stage costumes of the 20th century: Elton John and Stevie Wonder also appreciated his ability to communicate right to the back row of the top circle.

David Bowie performing as Ziggy Stardust at the Hammersmith Odeon, London, 1973, in a “woodland creatures” costume designed by Kansai Yamamoto. Photograph: Debi Doss/Getty Images

Yamamoto had had a hard road to reach success. He was born in Yokohama, eldest of three sons of a tailor who divorced their mother when Yamamoto was seven. The family was left so poor that the brothers were sent to a children’s home, and Yamamoto remembered looking into the lit windows of happy family homes, lost, lonely and hungry. He later lived with his father in Tokyo, helped him with sewing jobs, and learned to cut his own tight trousers to dress like his favourite movie actor.

He managed to get into Nihon University to study English literature, which should have secured him a safe middle-class future, but at 20 he abandoned the course because he wanted to express himself, wanted to recreate the beautiful birds he had seen on a trip to the jungles of New Guinea. This was a serious dropping-out; Yamamoto worked as a minimum-wage garment hand for Junko Koshino and Hisashi Hosono, designers attempting 60s western youth fashion in Japan, while teaching himself fashion.

He reunited with his mother, who was learning dressmaking in Yokohama, and through her class heard that the Bunka Fashion College Soen prize was open to non-students. He won it in 1967, and by 1971 had his own small company. Japan did not respond to basara fashion and he felt a freak there, hence the leap to London.

Yamamoto did found the Tokyo Designer Six group in 1973, with the achieved aim of setting up a Tokyo fashion week. His post-Bowie Paris debut in 1974 was a commercial failure, bankrupting him; after the oil crash, top-end ready-to-wear customers preferred the new natural. The next generation of international Japanese designers was all about the natural.

He persisted, showing in Paris until 1992, selling through the Kansai Boutique there. During their collaboration, Bowie had pointed him to another way forward: fashion as a live spectacle big show, and Yamamoto started producing them, staging Hello! Russia in Red Square, Moscow, in 1993 to a crowd of 120,000, then Hello! Vietnam in 1995 and Hello! India in 1997. He kept his name on licensed goods and designed novel kimonos, but had never been in the business for the money, more the experiences, which came to include playing the murder victim in the 2003 film The Blue Light, and designing in 2010 the Skyliner train connecting Narita airport with Tokyo.

Kansai Yamamoto during a fashion show in 2012. Photograph: Minoru Iwasaki/AP

In his last decade, it felt as though the graphics and deliberate non-matching of current global fashion had at last had caught up with Yamamoto; in 2013, he designed for Lady Gaga, in-your-face pattern collages close to the Bowie era but digitally ink-jet printed; they had not dated a day, over the top as ever. The crashing imagery and joyous facepaint of his Fashion in Motion show at the Victoria & Albert museum that year still look totally modern. Only Bowie’s death in 2016 kept them from one last “supershow” together.

Yamamoto named one of his two daughters Mirai (Future) because she was born during his financial crash – she was his hope. She and her sister survive him.

• Kansai Nobuyoshi Iseya Yamamoto, fashion designer, born 8 February 1944; died 21 July 2020